A fascinating talk was given to a packed church by author Patrick Whitworth at the launch of his latest book, Three Wise Men from the East: The Cappadocian Fathers and the Search for Orthodoxy, on 21 May 2015.

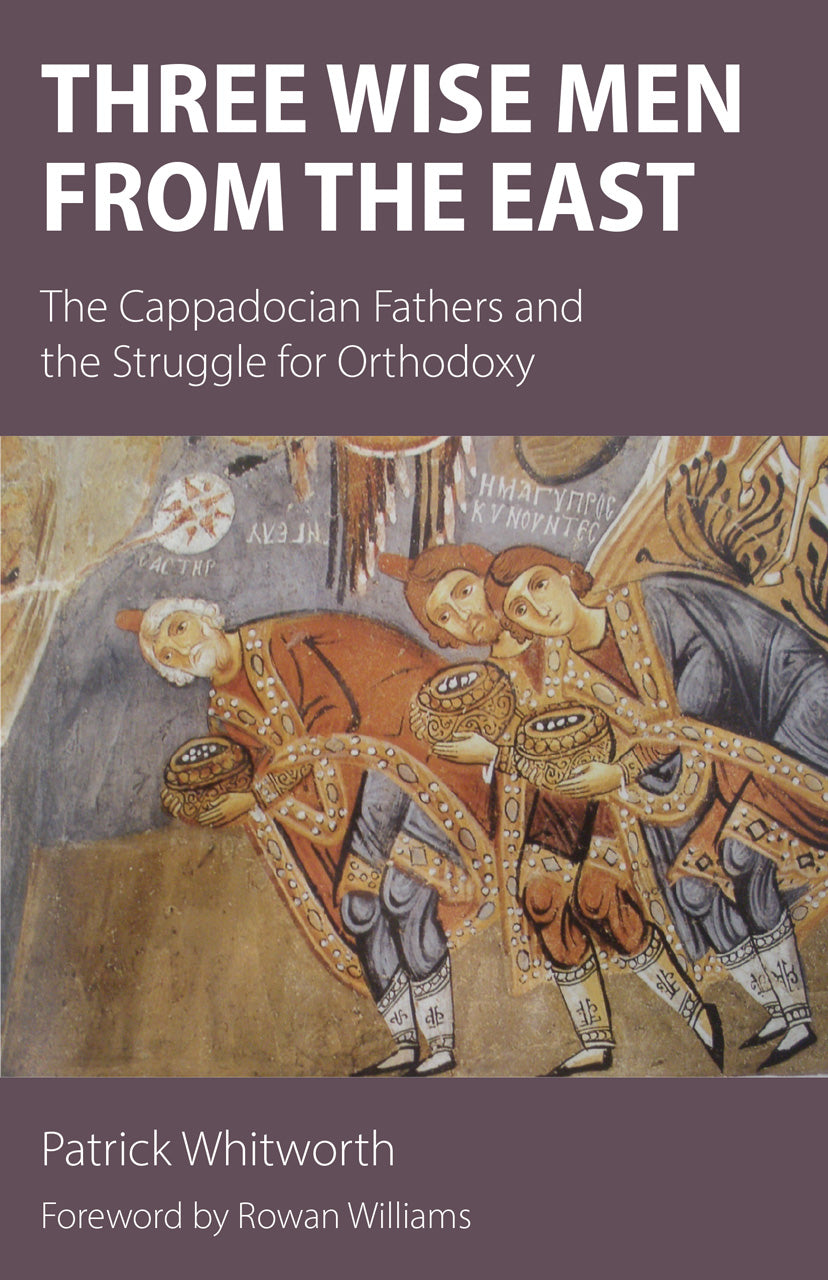

Today’s book launch is about THREE WISE MEN. Not these ones at the nativity—this is a fresco from the Dark Church in Goreme in Cappadocia, which is full of vivid frescoes of the life of Christ:

ABOVE: Fresco in the Dark Church in Goreme showing the Three Wise Men (Photo: Patrick Whitworth).

Nor is it about these Three Wise (or not so wise!) Men—Tom, Paul and myself three years ago in Cappadocia, May 2012.

ABOVE: Three (Un)Wise Men in Cappadocia.

But it is about these Three Wise Men: Basil of Caesarea, his younger brother Gregory of Nyssa and their friend Gregory of Nazianzus. All three were bishops in what we would now call the Greek Orthodox Church in fourth-century Cappadocia, in the Roman Empire of the East, in the period from AD 330–395.

ABOVE: Gregory of Nyssa, Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nazianzus.

It was the Age of the Emperor Constantine, and his successors, during which the church went through a fundamental change of status: from a persecuted community in AD 305 under Diocletian—through the sudden change after the Battle of Milvian Bridge on 28 October 312 when Constantine took charge in the West—to become virtually the Empire’s new religion. In The Edict of Milan in 315, Christians were given freedom to worship in the Empire.

But theological storm clouds were gathering. In Alexandria, a priest called Arius with a popular following began a movement, soon to be called Arianism, in which he claimed that Christ was inferior to the Father and was himself created, with the claim that there was a time when he, Christ, was not. It caused a controversy, which generated a schism, which rocked the church; so Constantine decided to call a Council of all the Eastern Bishops and some from the West to decide what the scriptures taught and what the Church believed about the Trinity. It was the First Ecumenical Council of the Church. It met at Nicaea in 325, present day Iznick, south of Constantinople on the shores of a beautiful inland lake at the Imperial Palace.

The result was the Nicene Creed, and every Sunday here we say the Nicene Creed in which we say of Christ that he is of one substance/being with the Father (homoousios). But after the Council, subsequent Emperors—notably Constantius, Julian and Valens—rowed back from the decision, in the period from 325–381. During this time the Cappadocians—Basil, Gregory and Gregory—sought to define the doctrine of the Trinity in new language, upholding Nicaea and developing it further. The language they used and developed was of one common substance in the Godhead, but three individuated “hypostases”.

All of them were highly educated, well-born, privileged in background, deeply devout and profound in theological thought. After Basil’s four year University Education in the Schools of Athens, he returned to Cappadocia, did a tour of monastic and eremitic communities of the near east. He was then baptised and ordained priest in 364 and then—given his education, leadership skills—was made Archbishop of Caesarea in 370. He wrote copiously; against the compromises of the church and imperial government with Arianism; a voluminous correspondence—second only to Cicero in quantity of letters—letters about doctrine, pastoral care, to young leaders, letters of consolation to grieving parents or spouses, letters of reproof to wayward monks or clerics. He wrote the first work on the Holy Spirit, blistering homilies on the care of the poor, social justice, rules for the ascetic communities, on science and creation. He founded a community or hospice for the poor and dying with his own money called the Basiliad. He was one of the foremost leaders of the Eastern Church for 10 years; he died aged 49 in 379.

His moment of brilliance occurred when summoned to Constantinople from his five-year retreat in a monastic community to minister at a Chapel in the city to the minority Nicene community. The result: his unsurpassed Theological Orations—five sublime Orations on the Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit—unsurpassed in their beauty, orthodoxy and expression. Summoned by the new Spanish Emperor Theodosius who came to the rescue of the Empire defeated by the Goths, he was made Bishop of Constantinople presiding at the Council that re-established Orthodoxy in 380/381. But for various reasons he only lasted a year, returning to his family estate to live as a hermit, polish his Orations and write a long autobiographical poem. He died in 390, aged 60.

And lastly Gregory of Nyssa: if Basil was the great church leader and Nazianzus the sensitive theologian, Nyssa was the mystic. He wrote extensively for Orthodoxy. But at heart he was mystical; seeking God in the darkness of incomprehensibility, apophatic spirituality—meaning that God in Christ is known, but unknown; understood but always beyond understanding. He argued that we must put off the “garment of skin” to enable the ascent of the soul. He looked for sober inebriation through encounter with divine love; he was was at home in the Song of Songs. His famous Life of Moses is a narrative for the progress of every Christian in prayer, contemplation and experience. He wrote a Platonic account in the form of a letter and dialogue about his dying sister Macrina, encapsulating the destiny of man and echoing Plato’s Phaedo on the immortality of the soul.

The fascination of the Cappadocians is their interweaving of orthodoxy, contemplation, social justice and Christian hope expressed in Greek thought and terms. Their characters were very different, their theology—on the one hand united in orthodoxy on the Trinity, but also diverse in their expression of following and knowing the God whom they worshipped.

Like the first Wise Men depicted so beautifully in the frescos in the Dark Church in Goreme, they followed a star with three points: struggle for revealed truth (notably the Trinity), solitude in contemplation and prayer, and service to a world of very harsh realities.

Intrigued by these Three Wise Men from the East? Read more about the Cappadociain Fathers and the Struggle for Orthodoxy in the early church.

Patrick Whitworth is the author of Three Wise Men from the East and Gospel for the Outsider.

He read Modern History at Christ Church Oxford, and a Theology MA in Reformation Studies under T. H. L. Parker at Durham. He has spent over 30 years in Anglican Ministry, currently Rector of All Saints Weston Bath, Langridge and North Stoke. He is married to Olivia with four grown up children.