Image: Flickr/DVIDSHUB (CC BY)

For the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944, James Hagerty and Barry Hudd recall the brave ministry of Catholic military chaplains during Operation Overlord

The build-up and crossing

Fr Dermot Donnelly, an Irish Jesuit, was “leading a fairly quiet life” in Norfolk until March 1944, when he was transferred to act as padre for a medical unit based in southern England. Under intense security, thousands of men endured strenuous physical exercises, arranged personal equipment, and practised embarking and disembarking from landing craft. On 5 June, the original date for the invasion, they waited in the Solent “while…the huge invasion force of men, machines and vehicles was being loaded.”

The Irish Redemptorist Fr Dan Cummings, deployed with 3rd Irish Guards, gave Holy Communion to ‘a few devout soldiers’ and wrote ‘it is hard to realise that tomorrow is D-Day.’ ‘When the invasion begins’, he had written to his Superior, ‘will you ask the houses to say a weekly Mass for the chaplains and their men?’ He added, ‘I have no illusions about what lies ahead.’

Fr Donagh O’Brien, an Irish priest from the diocese of Southwark, recalled ‘we were all strung up, almost to breaking point’. As he passed the Isle of Wight and the English coast ‘faded away’, the Redemptorist Fr Gerard Costello wondered ‘if he would ever see this again’.

The first into battle were the airborne troops and their chaplains. In the early morning of D-Day, 3rd Parachute Brigade landed in Normandy. Fr Maurice McGowan of Westminster Diocese dropped with Airlanding 195th Field Ambulance and Fr William Briscoe of Shrewsbury Diocese dropped with 225th Parachute Field Ambulance. Fr James Kenny of Lancaster Diocese, with 224th Parachute Field Ambulance, dropped by parachute and was immediately caring for the wounded men. With a wounded man on his back, he led a party of paratroopers to safety after they had been cut off from their main group. Fr Joseph McVeigh of Westminster Diocese, attached to 8th Parachute Battalion, was captured when his glider crashed near an enemy position.

Sea crossing and the Normandy beaches

The bad weather made the sea very choppy and many men were seasick. Fr Thomas Holland, of Liverpool diocese and a Royal Navy chaplain, was in an accommodation ship loaded with sailors destined to crew landing craft. He climbed down a rope ladder over the side of a heaving ship on to a tossing landing craft while carrying his Mass kit and personal equipment.

The bad weather made the sea very choppy and many men were seasick. Fr Thomas Holland, of Liverpool diocese and a Royal Navy chaplain, was in an accommodation ship loaded with sailors destined to crew landing craft. He climbed down a rope ladder over the side of a heaving ship on to a tossing landing craft while carrying his Mass kit and personal equipment.

On Juno Beach he was given a tent next to a Beaufors gun emplacement and operated as the only Catholic chaplain. For ministering to the sailors and marines on assault vessels, as they landed and dug in under heavy fire, Fr Holland was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for ‘his gallantry, skill determination and undaunted devotion to duty during the Allied Forces on the coast of Normandy’.

After a rough crossing, naval chaplain Fr Costello landed with 48 Royal Marine Commando on Juno Beach where many Canadians were lying dead or wounded. An Anglican chaplain was among the wounded and an officer was in a state of deep shock having seen four of his men blown to pieces. In the midst of fierce German opposition, Fr Costello tended the wounded and prayed with the frightened. In the following days he buried British, French and German dead.

On one occasion he was on an ammunition trailer which attracted German fire. He was the only chaplain to emerge unscathed from Juno and accompanied the Allied advance through Normandy, pausing on one occasion to help a German chaplain bury his dead. Fr Cyril (Paddy) Crean of the Diocese of Dublin, senior chaplain to an armoured brigade, wrote that ‘the trip over in that enormous convoy was a thrilling sight’. He disembarked and ‘waded in… with all my kit on my back…in water waist deep and into the most incredible sight in history’. Amidst the confusion, danger, noise, movement, corpses and wounded men he began the next stage in his ministry.

Fr Alan Birmingham, an Irish Jesuit, was with a Landing Craft Force and having waded in up to his shoulders in water, he was directed to a dressing station where there were already dead and wounded. His Irish confrère, Dermot Donnelly SJ, was on a Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) with many sea-sick soldiers. Opposition on the beach had been swept aside but during the next day he spent ‘almost all the time burying the dead’.

‘Sitting ducks on the beach’

Fr Jimmy O’Sullivan, a Cork priest of the Australian Diocese of Sandhurst, landed with 6th Duke of Wellingtons, who ‘were like sitting ducks’ to German defenders. The padre tended many wounded and covered the dead with their gas capes. Fr Dan Cummings and his unit dug trenches as they were shelled and he administered sacramental and material comfort where he could, including to captured Germans. He wrote: ‘If we are spared to return, we shall all be the better for the experience. Living close to death is an experience which changes your mind irrevocably… The years will not be long enough to thank God for his mercies’.

Officers faced the fear of battle, bore the responsibility of command and relied heavily on their padres. The commander of 9th Durham Light Infantry admitted he depended on his experienced chaplain, Fr Jack Devine of Elphin Diocese, to keep morale and spirits high among the ranks. As RAF chaplains were not allowed on flying missions, they were not involved in early D-Day operations but Redemptorist Fr Oliver Conroy and Jesuit Fr Peter Blake were with 2nd Tactical Air Force which bombed German defences and tactical positions. They were both in France later in June 1944.

Tendering to their flocks The continuous build-up of men and materiel may have created logistical problems on the beaches but it presented chaplains with opportunities to tender to their flocks, all of whom were in relatively close proximity. The breakout into the ‘bocage country’, however, ended this arrangement as chaplains began to follow troops all over Normandy and on towards Germany.

Chaplain casualties

In the midst of the invasion’s death and destruction, it was only to be expected that chaplains would be killed and wounded. In all 22 army chaplains of all denominations were killed between D-Day and the end of September 1944. Fr John Meagher of Hexham and Newcastle Diocese, attached to 7th Armoured Division, was injured by strafing from enemy aircraft and Frs Philip Dare, William Briscoe, Alphonsus Coia, Michael Murphy, Jack Devine, John Corbett and Hugh Donaghey were all wounded. As naval units ‘took root’ along the coast, Fr Holland’s ‘land parish’ stretched from Ouistreham to Granville.

Naval casualties were not as heavy as army units and Fr Holland noted that ‘only a tiny fraction was called upon for the supreme sacrifice’. As the Allies moved in land so too did Fr Holland and near Bayeux he saw both General De Gaulle and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In his memoirs, Bishop Holland paid tribute to the planning genius behind Overlord and the heroism of all the Allied forces. He also acknowledged the work of the padres and the ‘supreme charity towards those who fell’.

Lest We Forget

Four Catholic priests died in Operation Overlord. On D-Day +1, Fr Peter Firth of the Diocese of Lancaster, had just waved to a soldier when he was shot and died instantly. He was buried in an orchard by the parish church of Hermanville-sur-Mer and was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre.

Fr Gerard Nesbitt, of Hexham and Newcastle Diocese, had been with the Durham Light Infantry since 1941 and had served with them in the Middle East, North Africa and Sicily. On 5 July 1944 he was killed by a shell explosion while conducting a funeral. One of those he was burying was an Anglican chaplain, killed when his motorcycle collided with a Bren Gun Carrier. The two chaplains now lie side-by-side in the Jerusalem War Cemetery southeast of Bayeux. Fr Nesbitt was awarded a posthumous Croix de Guerre.

Fr Patrick McMahon, an Irish Columban, was killed on 14 August 1944. He had gone to rescue a wounded Canadian soldier but on the return journey his ambulance was hit by a shell. He was buried in the churchyard at Ussy following a requiem Mass attended by 50 Allied chaplains. He is buried in Ussy War Cemetery.

Following the withdrawal of ‘the Dukes’, Fr O’Sullivan was transferred to 1st Leicesters on a sector close to Lille. On 14 September, his first night with the battalion, he was asked to carry out a communications duty which involved him speaking French. As he did not speak French, Fr O’Sullivan was replaced by Fr Gerard Barry of Liverpool Diocese attached to 8th Royal Scots. Fr Barry was subsequently killed while sheltering in a deserted farmhouse. He is buried in Geel War Cemetery, Belgium.

Further Reading

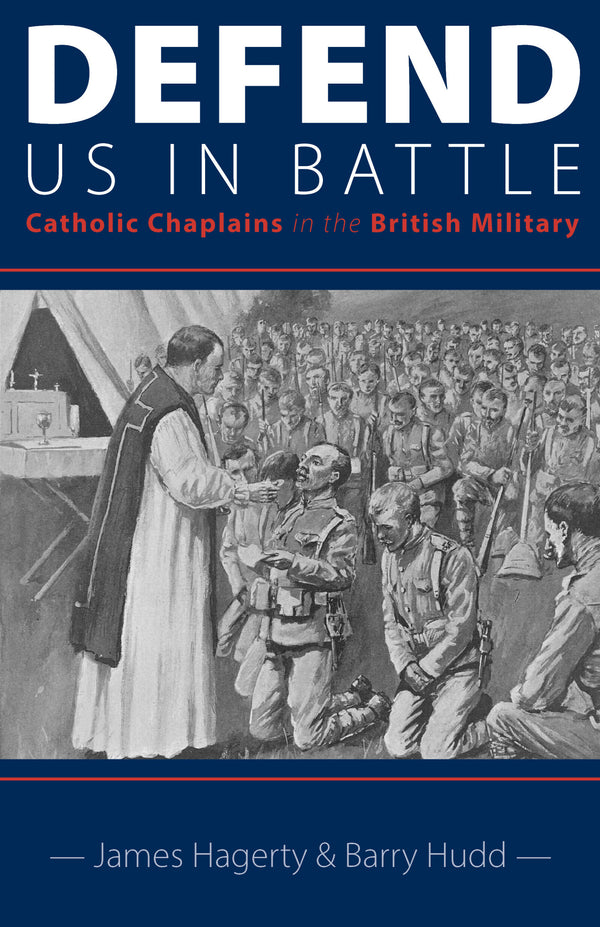

Sacristy Press has published Defend Us in Battle: Catholic Chaplains in the British Military by James Hagerty and Barry Hudd. A full review will be in the 7 June issue of the Universe.

Copyright © Universe Catholic Weekly. Reproduced with permission.