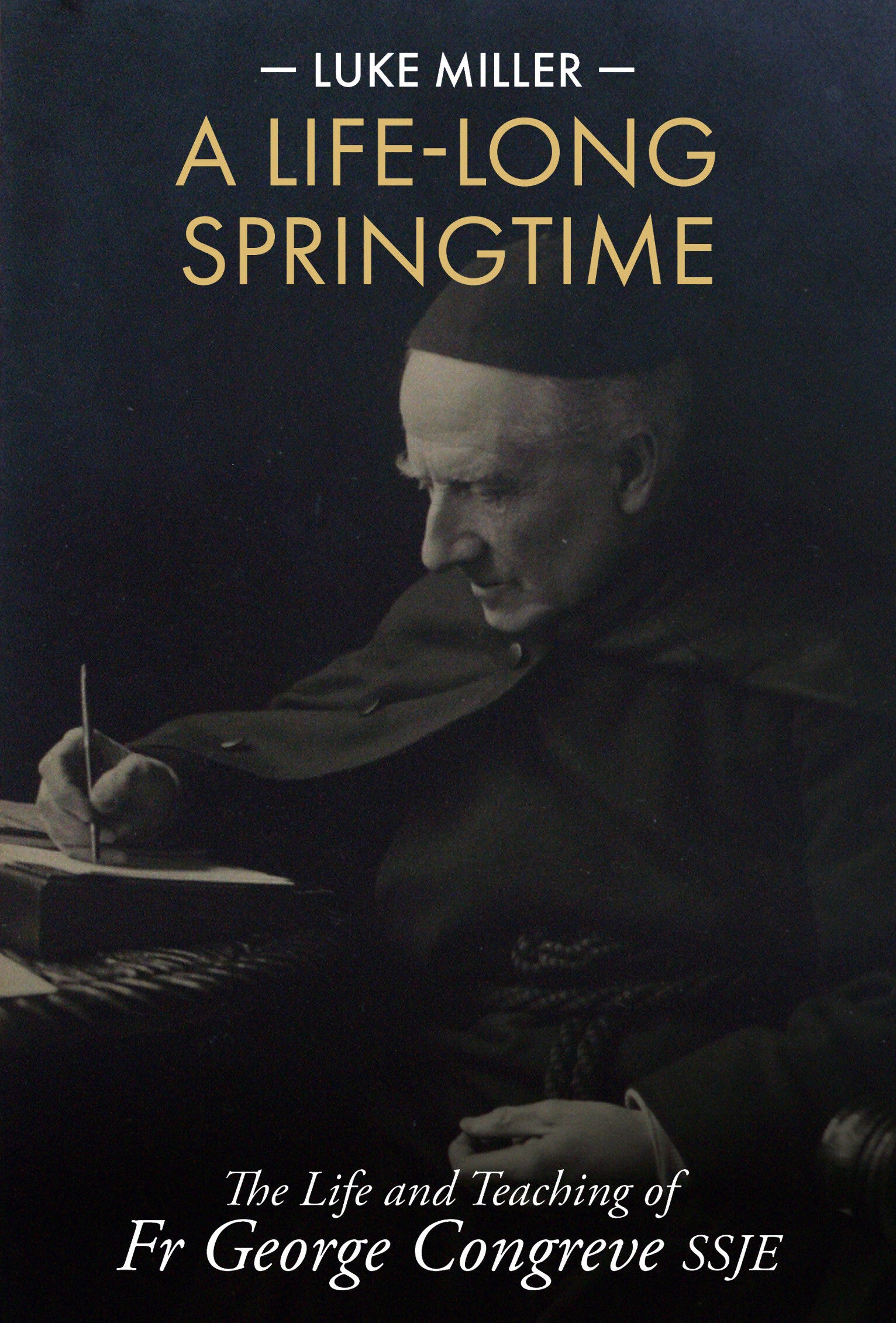

As part of our April focus on Christian history Luke Miller, author of A Life-Long Springtime: The Life and Teaching of Fr George Congreve SSJE, discusses Fr Congreve’s views on Christ’s role in human history.

In the late 1870s Russia went to war in the Balkans, partly to re-establish its presence on the Black Sea following the Crimean War, and partly to support the emerging Orthodox Balkan nations throwing off the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was not in the interests of the Great Powers that Russia should seize Constantinople, and by 1878 it looked as if Britain might be dragged into a war which had been marked by atrocities. In Oxford Richard Meux Benson, the Superior of the Cowley Fathers, an ‘institute’ of Anglican Mission Priests who lived under Religious Vows, thought that he discerned the birth pangs of a new age. He wrote: “We learn of the drawing near to war. I hope it will call the English nation out of this miserable life of self-indulgence. We must pray God garners to give us some fresh recruits for our own military movements.” By this Benson meant the warfare of the soul against evil; a sense used by his Assistant Superior, Fr George Congreve, who wrote of a nun who died of natural causes during the Boer War: “She has fallen in war: that is an honourable way to slip out of the probation of life—the Religious Life used to be called—“the warfare” —militia.”

nations throwing off the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was not in the interests of the Great Powers that Russia should seize Constantinople, and by 1878 it looked as if Britain might be dragged into a war which had been marked by atrocities. In Oxford Richard Meux Benson, the Superior of the Cowley Fathers, an ‘institute’ of Anglican Mission Priests who lived under Religious Vows, thought that he discerned the birth pangs of a new age. He wrote: “We learn of the drawing near to war. I hope it will call the English nation out of this miserable life of self-indulgence. We must pray God garners to give us some fresh recruits for our own military movements.” By this Benson meant the warfare of the soul against evil; a sense used by his Assistant Superior, Fr George Congreve, who wrote of a nun who died of natural causes during the Boer War: “She has fallen in war: that is an honourable way to slip out of the probation of life—the Religious Life used to be called—“the warfare” —militia.”

Congreve came from a family with a long history – it has been said of the Congreves that they are one of the very few families who “extended their line beyond the Norman Conquest.” An ancestor was the famous playwright William Congreve, and there were many eminent military Congreves, including another William, “Squibs” Congreve, the inventor of the Congreve Rocket, the first battlefield ballistic missile.

The discipline of History might be thought of as the ordering and interpretation of the events of the past for some purpose. For a Marxist, History will show the struggles of the Classes, the triumph of the Proletariat and the ushering in of the Perpetual Revolution. A Whig will trace the development of humanity from good to better. Other patterns are possible to assert, as when Oswald Spengler wrote of the rise and fall of cultures. Those who reject such determinism attempt to find patterns which nevertheless offer structure and the ability to understand the present, or even offer a guide to the future. (Though when Isaac Asimov in his series of Foundation novels proposed a fictional world in which scientific History was so advanced it could accurately predict the course of events he returned to determinism.)

There is a lot of history in the Bible, and much debate about it. St Luke begins his gospel with a statement of historical intent:

Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. With this in mind, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I too decided to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught. (NIV)

The things ‘fulfilled among us’ were the events which Christians call the Incarnation: that in Jesus Christ, a man born in Nazareth ‘in the days of Herod the King’, God entered into human history. This event is the fulcrum around which all history turns, and is the source, for the Christian of the meaning of events. In a retreat given over the turn of 1879 and 1880 Congreve wrote:

Not only is the incarnation a fact of history, a fact which still exists and is as powerful as ever, but . . . it is the very basis of all reality, of every substance of all existence. By Christ all things were made . . . all history is but the glory of the working out of His purpose, who, being God was made man.

This Christian reading of history is reflected in the way in which Christians came to date events not from the years of the Consuls of the Roman Empire or the regnal years of monarchs, but simply from the date of the birth of Christ. Sometimes calendrists delight to point out that since Herod the Great died in 4BC, Dionysius Exiguus, who began 247 years after the accession of the Emperor Diocletian to date events not as Anno Diocletiani but as 531 Anno Domini, got it wrong by five years (there is no year 0 AD or BC, which is why the millennium should have been celebrated on 1 January 2001). This is however to miss the point Dionysius was making. Fr Congreve asserted both the fact of the incarnation, but also its impact as the event which gives purpose to all history, even as it transcends history, making the exact dating less important than the fact of dating:

Our Lord’s Incarnaton is a fact of history, … it really happened at a particular hour on a particular day, but let us consider also that He took man’s nature to be our Mediator; not to do a certain work of mediation between us and the Father once for all, and then it was done with, but that by the eternal union of the two natures [of God and man] He himself is our Mediator – not was, but is. By His very existence He abides forever our Mediator.

His Incarnation was not an act of grace which we must go back 1900 years to contemplate. It is an eternal act and abides. Jesus at the right hand of God has an eternal relation to you; the gulf is bridged over, for the everlasting God is made man. Christ is God and man, and in Christ you are reconciled to God. Salvation is not a mere possible thing, it is an actual state given in Christ by the sacraments. We find it actual and real by treating it as a reality; we only lose it by treating it as a pious imagination.

History needs eternity if it is to have meaning beyond the emptiness TS Eliot articulated in The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock: “mornings evenings afternoons, / I have measured out my life in coffee spoons” and the ennui that CS Lewis criticised as “term holidays term holidays till we leave school and then work work work until we die.” It is well observed that there are no such things as ‘historical facts’, simply events which the specific historian argues are meaningful. Yet in the face of eternity, all individual actions and lives are evacuated of meaning. For Congreve history and eternity are brought together in Christ such that eternity gives purpose and meaning to our individual lives and their manifold events. Not only are the events of the time-bounded world thus given an order which makes them comprehensible, but at the same time and paradoxically, they are made meaningful precisely because of their connexion with eternity.

Not for nothing therefore, do we order our approach to history around the incarnation.

Luke Miller is Archdeacon of London. As Faith & Belief Sector lead for London Resilience, he has been involved in many of the major incidents in the capital over the last few years and the pandemic response and has been appointed a member of the London Recovery Board. He was appointed a Chaplain to the Queen in 2020. His book A Life-Long Springtime is being featured as part of our April #ThemeOfTheMonth: Christian History. You can get your copy here!