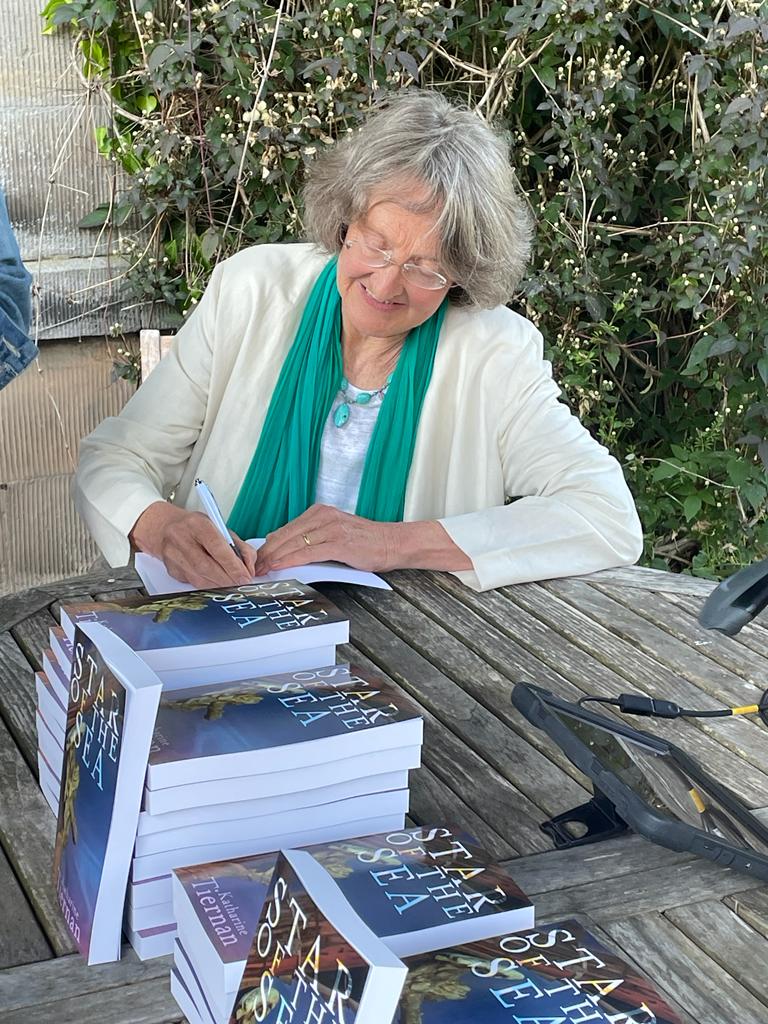

GUEST BLOG: Katharine Tiernan explores the origins of her family and their exploits in the Age of Sail. Here is the captivating talk Katharine gave at the book launch in Northumberland.

One of the first things I had to get used to as a child were my new best friends – the family portraits. Whenever I went up or down the stairs, into my bedroom, along the corridors, there they were, their eyes following my every move. I don’t know how the artists did it, but those eyes follow you wherever you go. Wherever you stand. They were always there, in their stiff clothes and gilt frames, always watching, always judging. I took to running downstairs very fast.

A lot of years later, I’ve decided it’s time to return their gaze; to stop running and look back at my family. To look at the lives behind the portraits. Many of them date from the nineteenth century. We know quite a lot about the family during Victorian times, so that might have been the smart option. But it felt a bit too close to me, a bit too familiar. Looking further back, to the eighteenth century, there were rumours of Jacobites in the family, a legend of a Rebel Ring, still held by a descendant. It sounded romantic, and I decided to start there.

I was very fortunate that the basic task of constructing the family tree had already been done for me, and its authors generously gave me access to it. But although the names were there, next to nothing was known about those people during the period. I had to embark on a wider search, deciphering wills and documents, discovering the miracle of the National Archive, and the newspaper archives and much more.

At the same time as the family research I had to bring myself up to speed on the eighteenth century. I’m good on the Tudors, thanks to Wolf Hall and all the rest, and pretty good on the Victorians. But the eighteenth century was a bit of a blank. I found it unexpectedly gripping. Why had I never understood how extraordinary a time it was? That it was where it all began, where colonial wars and explorations shaped the nascent British Empire and trade started to transform everyday life.

Of course I was coming late to the party. As we become more aware of the legacy of the UK’s colonial past, many people are looking back to find out what their eighteenth-century ancestors were up to. And where their money came from. It was a relief to discover that the slave trade did not feature directly in the Cresswell story, although one could argue that commerce of the later eighteenth century was stained indirectly with the same association.

What did seem clear to me, as I learned more about the century, was that what I was discovering about the history of my ancestors, as well as personal stories of love and tragedy, was in a real way a microcosm of the social history of the time. And I hope that this gives the novel a resonance beyond the bounds of personal, family interest.

So, what was their story? Of course you have to read the novel to find out, but here’s a quick flavour.

The Cresswells of the eighteenth century were minor gentry with an estate and an ancient pele tower. The tower was, and is, at Cresswell but the site of the old Cresswell Hall is now a caravan park. If you don’t know it, Cresswell is a small seaside village near Ashington in the south of Northumberland.

The Cresswells’ main claim to fame was their longevity. They were part of the Norman land grab that took place in the north of England in the twelfth century and could claim to have been in residence ever since. One of them married an illegitimate daughter of Edward IV, so they were able to bask in a distant connection to royalty.

By the eighteenth century, however, the family name was coming perilously close to extinction. They managed to survive their involvement with the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 and demolished the family chapel to erase all traces of Papism from their record. But later in the eighteenth century the longed-for son and heir came close to gambling the estate away on the racetrack. Having eloped with a penniless curate’s daughter, he died young, leaving twin daughters. What was to become of them, and how was the family name to continue?

The unexpected saviour of the Cresswells turned out to be the man who married our heroine, Elizabeth Cresswell - one of eight Cresswell sisters. His family were smugglers. He started life as a deckhand.

His name was John Addison. Like his contemporary, James Cook, he served as an apprentice at 12 years old on the Whitby colliers, shipping Newcastle coal to London. When Cook finished his apprenticeship he joined the navy. John Addison started to buy shares in ships. For both men, the new age of sail offered a completely new route to wealth and social status. Cook was the son of an agricultural labourer; he was to become a naval commander and famous explorer. John Addison’s career was equally successful but more unconventional. I had suspicions. They were finally confirmed when I tracked down a vital document in the Admiralty records. During the Seven Years War (1756 – 1763) the Admiralty issued Letters of Marque licensing merchant ships to attack and capture enemy shipping for their own profit. It was regulated – shipmasters had to notify the Admiralty of their captures and have them certified as enemy shipping. But after that, all the profit was theirs. It was licensed piracy, otherwise known as privateering. And on a memorable day for a history nerd, there it was, in front of me, John Addison’s Letter of Marque.

High Court of Admiralty: Prize Court: Registers of Declarations for Letters of Marque

Against France

Commander: John Addison.

Ship: Friends Desire.

Burden: 400 tons.

Crew: 80.

Owners: John Addison.

Lieutenant: John Broderick.

Gunner: Andrew Harper.

Boatswain: Hezekiel Newmatch.

Carpenter: John Hutchinson.

Surgeon: John Addison.

Cook: Thomas Presswick.

Armament: 10 carriage guns.

Date July 1756

It was one of those moments that make you forget all the fruitless hours ploughing through old documents.

So John Addison was a pirate, and a very good one. At the end of the Seven Years War he bought himself the Manor of Appleton-le-Street, not far from Castle Howard with his profits. He was in a position to look for a wife, and Elizabeth Cresswell was the woman he chose. She was twenty eight and prepared to overlook his humble origins for the sake of escaping spinsterhood.

For John Addison, marrying into a gentry family like the Cresswells opened the doors to patronage. With Elizabeth at his side, he formed a relationship with the noble Mulgrave family, lords of Mulgrave Castle outside Whitby. The Mulgraves provided capital and commissions for John Addison’s shipping business. During the American war, Lord Mulgrave was Paymaster General for the Armed Forces. Both sides made a fortune from shipping and naval supplying. Patronage was not disgraceful in the eighteenth century. It was how things worked.

John and Elizabeth’s was a successful marriage, in all but one respect. They were childless. Ever resourceful, John Addison turned to the Cresswell family in his search for posterity. He found ways to make it his own, from paying off the debts on the estate to an arranged marriage between his nephew and the Cresswell heiress. The family continued – through the female line.

Which takes us to another thread in the novel; the woman’s side of the story. Part of that relates to a well-known ghostly legend associated with Cresswell tower, of a woman in white who haunts the shore. Long ago, the daughter of the house fell in love with a Danish prince rescued from a shipwreck on Druridge Bay at Cresswell. When the prince returned to claim her hand, her brothers fell upon him and murdered him for his gold. She leapt from the top of the tower to try and save him and died in his arms. Whenever stormy weather is blowing, the legend goes, the white lady of the tower can be seen on the beach, running to and fro, calling for her lover.

In the novel, Elizabeth Cresswell becomes aware of the spirit’s presence early in her childhood. Like the old statue of the Virgin Mary, Stella Maris, in the church nearby, it supports her through the hard knocks of her life. The nurturing and enduring feminine presence both represent is a counterpoint to the violence of the struggle for wealth and power that preoccupied our eighteenth-century ancestors – or, to be more precise, our male ancestors. Eighteenth century women were excluded from property ownership and politics, from business and the professions. Marriage was the only route to an independent life. Many women spent their adult lives struggling with childbirth and enduring the shockingly high rates of infant and child mortality that haunted the nursery. Grace Cresswell, Elizabeth’s mother, buried six sons in infancy. It was just as dangerous for the mothers, irrespective of class. Two of the women who feature in the story died in their first confinement. The novel seeks to tell their story as well.

There is a postscript to Elizabeth’s story. For her, the relationship with the Mulgraves was never just about business. The first hint of a more romantic connection comes in codicil to her will. It refers to a diamond edged miniature portrait of Constantine John, Lord Mulgrave, which she bequeathed to his daughter. I was intrigued. What was going on here? Why was his portrait so special to her? The clues came from another will – the will of Lord Mulgrave himself. Constantine John was a fascinating man in his own right, a close friend of Joseph Banks who led a voyage of exploration to the North Pole, a distinguished naval commander and a leading politician. But he was forced to resign his government positions due to a prolonged wasting disease, which was probably TB. He died in Spa, near Liege, where he would have been seeking a cure. His death was clearly unexpected, as the will is a rushed affair. It is witnessed by two local attorneys, his man-servant Louis Catt – and by Elizabeth Addison. My suspicions of a liaison, later in life when both she and Constantine had been widowed, seemed to be confirmed. It must have been her great adventure, travelling to France with Constantine – and how tragic for her to lose him. In his will he left her five thousand pounds, in gratitude for her ‘unexampled goodness.’ It was a poignant moment of discovery.

Elizabeth returned to England and ended her days at Cresswell. There is a memorial to her in Woodhorn Church. It was erected by her great-nephew, Addison John Cresswell, in remembrance of her’ unbounded kindness’ to him.

Elizabeth’s portrait is one of those hanging on the stairs inside the house. It is a full-length portrait of her taken in later life, in dowager grey silk. It gives her a grim look. I was scared of her as a child. It’s been an extraordinary and moving experience to make the acquaintance of the woman behind the portrait, this woman of unexampled goodness and unbounded kindness.

So – that’s a bit about the Cresswells, and a little taste of the story. I hope you’ll read the novel and enjoy it all!

Star of the Sea is available from all good independent bookshops, and direct from the publisher Sacristy Press.